Daria Dugina, Filosofia como Destino, traduzido de Daria Dugina, Philosophy as Destiny, escrito por Natalia Melentyeva, mãe de Daria.

Discurso na entrega a Daria Dugina do diploma de vencedora do prémio A Face da Nação. Lutadores na frente invisível 2022, em 2 de Fevereiro de 2023. Speech

on the occasion of the presentation of a diploma to the winner of the

award The Face of the Nation. Fighters of the Invisible Front 2022 to

Daria Alexandrovna Dugina, 2 February 2023.

15-XII-1992 a 20-VIII-2022...........

Tradução minha, da tradução inglesa por Lorenzo Maria Pacini, e que encontra no fim:

A Filosofia como Destino.

«A vida no mundo actual pressupõe e até exige um enorme esforço da nossa parte não só nas questões mundanas e movimentos exteriores. Acima de tudo, exige um esforço da mente, do pensamento - um esforço mental, um "fazer mental" como era chamado na tradição monástica dos "santos padres", e esta praxis da mente é necessária não só para fazer uma "distinção", diacrisis, como diziam os platonistas gregos, para distinguir um do outro - o precioso do não precioso, o bom do mau, o casual do fatal, mas para algo muito maior e mais significativo...

Vivemos num mundo danificado, distorcido, numa civilização quebrada, cuja espinha dorsal está partida, assim como a sua percepção da superioridade vertical e hierárquica. Um esforço inteligente é necessário para restaurar as proporções deste mundo hierárquico inteligente, o modelo do qual foi criado [ou intuído...] por Platão, e isso é o Platonismo.

| |||

| Muita luz e amor para Daria Dugina Platonov, uma mulher extraordinária, barbaramente assassinada à bomba por uma agente dos serviços secretos ucranianos... | |

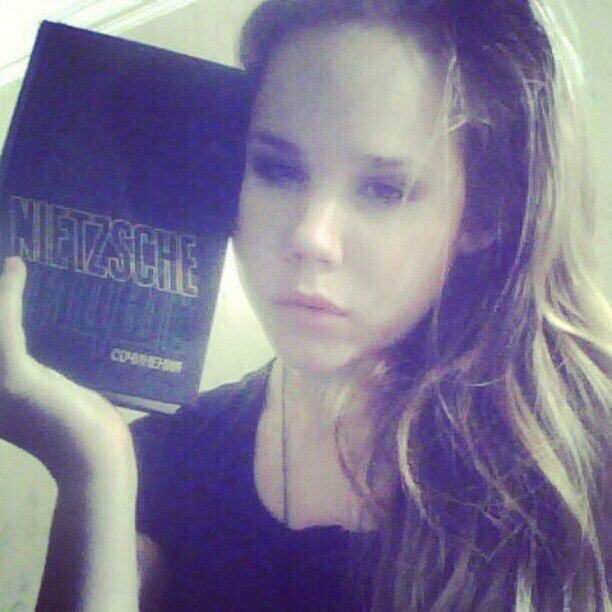

Daria Dugina escolheu o pseudónimo Platonov e dedicou-se ao estudo do platonismo e dos filósofos platónicos. O americano A. Whitehead disse uma vez que toda a filosofia do mundo não passa de anotações nas margens de Platão. Ao envolver-nos com o Platonismo - chegamos ao centro do tufão, ao coração do problema da geração do significado, da criação de estruturas de pensamento, da mente, da história, das culturas, das civilizações...

Dasha [Daria] sabia disso e escolheu deliberadamente esse caminho. O caminho da mente é perigoso. As pessoas temem a mente como o fogo. Em tempos antigos, as autoridades da cidade de Atenas mandaram executar o pensador mais sábio da Grécia e de toda a humanidade, Sócrates. O povo [cristão fanatizado] de Alexandria assassinou a filósofa neo-platónica Hipatia [qual Daria...] Actualmente, as elites do mundo ocidental odeiam o livre pensamento de uma forma cruel e totalitária. Matam e tencionam matar pensadores, filósofos, sábios, profetas, génios - todos aqueles que não pensam no destino da humanidade em uníssono com o grupo de vilões que se apoderaram do discurso global moderno, que estão prestes a encerrar completamente o Projecto Humano, transformando-o num clone, num computador, numa informação na nuvem. Daria Dugina sabia que este obscurantismo racional tinha de ser combatido, antes de mais, pela Mente: pensamento, ideia, conceito, projecto. Ela escolheu o platonismo como foco desta luta.

Platão criou um mundo inteligente e coerente de dois andares, no qual as ideias, os modelos, as formas das coisas e os acontecimentos do mundo flutuavam no andar de cima, enquanto no andar de baixo habitavam a matéria e as próprias coisas, as quais existiam contemplando as ideias-Logos e imitando-as como seus modelos celestiais. Assim se construiu a hierarquia do Céu e da Terra, uma hierarquia de ideias à cabeça da qual brilhava a ideia do Bem, ou do Um: o inexprimível, para além de tudo o que podia ou não podia ser pensado. O Platonismo descrevia uma estrutura intelectual e inteligente do mundo, aberta a partir de cima. Colocava o ser humano no centro de uma hierarquia vertical, como uma espécie de mediador entre os mundos. Ao contemplar as ideias, o ser humano assegurava a construção do mundo e que as coisas eram produzidas, ecoando os arquétipos celestes. Este modelo de mundo existe há milénios. As suas estruturas, hierarquias, escalas de ascensão e de descida reflectem-se em todas as religiões do mundo. Nele, o ser humano é um "ser que ascende" (em direcção ao Espírito, ao Bem, à Verdade, à Beleza, à Justiça, ao Um) e, por vezes, retorna (o Mito da Caverna de Platão) e volta a subir a escada de Jacob, a escada da perfeição espiritual. Esta ascensão do homem, a sua perfeição, a sua transubstanciação, é o objectivo da vida.

No entanto, o mundo deteriora-se com o tempo, o ser humano torna-se insensato. De uma forma ou de outra, veio a Modernidade e depois a Pós-Modernidade, que é em parte aquilo em que nos encontramos hoje. O pós-modernista francês do século XX Gilles Deleuze falsifica Platão - apenas nas margens dos seus escritos - distorcendo fundamentalmente a imagem platónica do mundo. Deleuze argumenta que o platonismo não falava do dualismo entre ideias e matéria, mas da dualidade da própria matéria: a que acolhe as ideias, isto é, copia, e a que evita completamente a influência das ideias, esconde-se delas, escapa à influência do modelo inteligente, o Logos. No mundo, diz-nos o nosso mais popular filósofo ocidental [Deleuze], há coisas que se escapam, evitando qualquer forma, qualquer definição. E chama a isso "puro devir", "infinito", "sombra da cópia", "cópia sem original" ou "simulacro". Segundo Deleuze, essas coisas e pessoas indefiníveis, que escapam à ideia, ao Logos, não são completamente sem medida, mas essa medida não está acima delas, mas abaixo delas, no subsolo da sua existência. Não permanecem à sombra do Criador Único, dos mais altos significados celestiais, mas sob o feitiço, a hipnose de um elemento louco que vive abaixo daquela ordem que no Universo platónico as coisas recebem do Logos, do mundo da Mente e das ideias.

Os dois mundos de Deleuze: cópias e simulacros.

Deleuze estabelece assim dois mundos: um regido pela Mente mundana, que recebe modelos e formas das esferas celestes, e este mundo aparece a Deleuze como decrépito, não livre, não dinâmico, totalitário. É o mundo de uma realidade fixa, de uma certeza fixa, e por isso o mundo das "pausas" e das "paragens", com uma linguagem desajeitada para o descrever, para falar dele.

O segundo mundo, novo e belo, vem em auxílio do antigo, trazendo consigo significados fluidos, um elemento de fluxo, leve, e um "devir rebelde" sem pausas e paragens.

Através da imobilidade e da rigidez do velho mundo hierárquico das ideias e das coisas (não é difícil adivinhar que se trata do mundo platónico dos duplos argumentos), o segundo mundo de Deleuze, o mundo do devir paradoxal, surge como um fantasma, onde tudo é fluido ao ponto de os significados de passado e futuro serem idênticos, onde o antes e o depois, o mais e o menos, a causa e o efeito, o excesso e a deficiência, o crime e o castigo se fundem numa inexplicável concórdia e inter-transformação. Entramos num mundo sem limites que são transgredidos - daí o mundo do crime, da ilegalidade. É um mundo de reversibilidade mútua dos acontecimentos, ou seja, um lugar onde a razão é problematizada. Deleuze gosta da ideia de que, a par das coisas e dos seres formalizados, existem acontecimentos indeterminados e que, à sua superfície, se agitam acontecimentos ainda mais pequenos, a que chama "efeitos". Os efeitos são fluidos, leves, não fundamentados, arbitrários, espontâneos.

O ser humano como acontecimento

"O que é uma ferida na superfície do corpo?", interroga-se Deleuze. É uma coisa densa com o seu próprio estatuto? Será um efeito, um pequeno acontecimento que "nem sequer existe, mas apenas torna-se, persiste durante algum tempo na sua manifestação", e possui um mínimo de ser.

O que é que nós próprios somos? Não será a vida humana, incluindo o nosso eu, o nosso cume interior, que veneramos como sujeito, o nosso mundo, o nosso sonho, sugere Deleuze, apenas uma agitação cega à superfície de um acontecimento qualquer? Somos apenas um ligeiro ranger na superfície do ser. Um som de papel, uma espécie de névoa que se move nos limites das coisas.

O que é o vermelho do ferro, o vermelho do rosto?, pergunta Deleuze. É uma mistura de vermelhos e verdes. Também nós somos misturas, misturando-nos, para o bem e para o mal, com as coisas.

O "mundo dos efeitos" de Deleuze mistura-se e espalha-se. Nele nos movemos num infinito Aeon de devir.

"Não há nenhum Todo no mundo", argumenta o mestre da retórica francesa, "que ordene e seja responsável pela metamorfose das coisas e de nós próprios. Não há razão no mundo". O que nos é pedido não é que sejamos, mas que deslizemos [E para isso os meios de informação, alinhados e vendidos, tanto manipulam...]

Caosmos

O mundo de Deleuze é uma viagem em direcção ao "Caosmos", com a perda de nomes e a negação de toda a permanência, incluindo o conhecimento (porque "a permanência precisa de paz e de Deus", como Deleuze observa, "e nós não podemos dar-vos isso"). É um universo sem verticalidade, onde o símbolo da árvore como eixo vertical e hierarquia é substituído pela imagem de um rizoma, um tubérculo como uma batata, que brota acidental e inconscientemente para o lado, para o lado, para baixo, por vezes até para cima. É o mundo do infinito, do apeiron (ἄπειρον) - o que os gregos antigos detestavam particularmente, por oposição ao limite, o peras (πέρας), que completava, fixava a coisa.

O devir deleuziano implica uma fusão da linguagem, onde os substantivos são varridos pelos verbos como entidades mais fluidas, e onde no devir tudo se dissolve e desaparece. O mundo real do devir de Deleuze é o mundo da linguagem que se desintegra e sofre mutações no processo dessa desintegração. Uma vez que o denotativo é abolido ainda antes da filosofia de Deleuze, no estruturalismo de F. de Saussure, do qual Deleuze se distancia, a realidade transforma-se nele numa residualidade puramente linguística, em que o tecido semântico, o campo de significação do ser, se dissolve e desaparece, envolvendo nessa extinção o Homem como proprietário e gestor da linguagem. Adquirida em puro devir, a pós-linguagem transforma-se num urro inexplicável - num clarão de "efeito" à superfície da suavidade fundida da matéria que desaba em profundezas infernais. Daria Dugina dedicou o seu ensaio Black Deleuze a Deleuze e tem-se referido frequentemente a ele e à sua filosofia nos seus discursos, intervenções e conferências.

Coisas Predatórias e o Sujeito Vazio Lda

O programa de dissolução do homem, de desestabilização e de dissolução do próprio mundo é hoje elaborado não só nos programas extravagantes e perversos da escola de Deleuze, mas também nos grupos filosóficos pós-deleuzianos de "realistas hiper-materialistas" ou "ontólogos orientados para o objecto" (OOO) ocidentais contemporâneos, como R. Negarestani, N. Land, G. Harman, R. Brassier, C. Meyasu e outros. Estes filósofos explicam que o ser humano, na filosofia ocidental clássica, aparece-nos injustificadamente como demasiado íntegro, autoritário, arrogante e presunçoso. No entanto, comparado com a inteligência artificial, por exemplo, é absolutamente imperfeito e intratável. Por conseguinte, é inútil e perigoso continuar a alimentar no homem a ilusão de ser o administrador do universo e o arquitecto do progresso social. O ser humano está demasiado sobrecarregado pelo Logos. Porque é que estamos tão seguros, perguntam os representantes da OOO, de que o homem é a medida das coisas, o polo principal da correlação? Há o Nada e a sua circularidade, que se chama "devir". A partir de agora, o mundo do ser anteriormente chamado "homem" caracteriza-se pela indeterminação, indefinição, fluidez, "permeabilidade", caoticidade, e isto diz respeito não só aos acontecimentos da sua vida, mas também ao estado do seu frágil e instável eu [cuja identidade e género é cada vez mais manipulada, e a origem espiritual e divina é escamoteada.]

Mas o que é verdadeiramente sólido e fiável no mundo são os objectos cósmicos, as coisas simples, a Terra, o seu núcleo, comprimido na prisão de uma crosta gelada. Os objectos, embora fenomenologicamente indemonstráveis, são também praticamente alcançáveis: se apenas extinguirmos o nosso Dasein [vir a ser] humano, revelar-se-ão a nós de uma forma completamente inesperada, muito provavelmente como monstros, de acordo com Graham Harman, do Realismo Estranho (Weird Realism). Enquanto a nossa presença humana ainda persiste, os númenos são inalcançáveis. Eles (os númenos, as coisas em si) vivem de uma forma radicalmente externa (infernal), inacessível para nós, e muito possivelmente bastante predatória, e nós tiramos partido disso, considerando-nos ingenuamente seus senhores e amantes, mas há uma grande rebelião das coisas que está para vir, como disse Bruno Latour. O homem não é nada, com todas as suas reivindicações, capacidades, projectos e ilusões efémeras; os objectos têm de ser libertados do homem, deixados livres para criar, para seguir os seus próprios caminhos e trajectórias cósmicas; o homem tem de ser retirado do caminho do núcleo da Terra, por exemplo, para libertar o demónio nuclear dentro da Terra, para que esta essência solar quente e brilhante se possa unir numa dança cósmica com o Sol - é isto que nos diz o filósofo americano nascido no Irão, Reza Negarestani, fazendo eco do filósofo britânico Nick Land.

Daria Dugina estudou muito cuidadosamente os textos dos ontologistas contemporâneos orientados para os objectos, polemizando com eles em artigos e discursos. Houve também um incidente curioso. Daria participou uma vez numa apresentação on-line do livro de Negarestani em Moscovo. Este incidente tornou-se conhecido porque, durante uma discussão intelectual, um dos admiradores de Dasha pediu-lhe a mão e o coração. Daria prometeu gentilmente considerar essa proposta, mas só depois de o pretendente de ideias conservadoras-tradicionalistas conseguir dominar a filosofia oposta à sua e aprender de cor a Ciclonopédia de R. Negarestani.

Ataque às superfícies.

O tema da insolvência e da vaidade do homem nos representantes, como mostrámos, está sincronizado com o da dissolução do ser humano em Deleuze, o filósofo subtil, no qual a verdadeira vontade é proclamada não para as coisas e os enormes corpos e objectos cósmicos, mas para os fracos efeitos de superfície de todas estas propriedades. Ao olharmos para o panorama da filosofia Ocidental moderna vemos diante de nós os diferentes flancos de uma frente única que ataca a nossa tradição espiritual - platónica, cristã, tradicional. Nesta invasão da filosofia Ocidental moderna sobre nós, não há verticais, não há hierarquias, nem formas, nem ideias, nem valores, nem objectos, nem essências, não há causas, não há qualidades, não há esquemas, não há objectivos, não há linguagem, não há profundidade, nem altura, nem liberdade, nem espírito, nem Deus [Yuval Hariri, do Fórum Económico Mundial, é outro destes propugnadores da Sombra]. Também não há lugar para o ser humano. É-lhe ordenado que não se aprofunde, que não olhe para o alto e para longe, que não sonhe, que não projecte, que não pense, mas que escorregue e se dissolva, que se agite e que não pense demasiado em si próprio. É-nos ordenado, até mesmo ordenado, que fiquemos à superfície das coisas, que deslizemos ao longo da superfície dos acontecimentos, que sigamos as tendências, que sigamos as agendas. [Tais as da Nova ordem do Fórum Económico Mundial, as das Cidades de 15 minutos, ou os desequilíbrios de género e identidade].

Guerra de Inteligências.

Eu disse "somos comandados"! Sim, é isso mesmo! Por detrás do suave sussurro do discurso selvagem de Deleuze, nós, tradicionalistas, sentimos o passo pesado do imperativo totalitário. Não significa isto que há alguém no mundo que compreende as regras que nos são oferecidas, e que no mundo não há ordens de coisas em si, mas ordens de interpretações? Sob a capa de um jogo filosófico aparentemente aleatório, são impostas exigências às coisas e a nós próprios, portanto princípios e regras pelos quais alguém nos cola a certos padrões de percepção e de comportamento? Sim, de facto, este é o caso, e os nossos adversários intelectuais do Ocidente compreendem-no. Tal como a lei cardinal da geopolítica afirma que "quem controla o Heartland (Eurásia) possui o mundo", também aqui a fórmula funciona: "quem controla o discurso, estabelece a meta-linguagem, controla tudo".

Serão os paradigmas - as chaves das visões do mundo, das civilizações e das culturas - conhecidos no Ocidente? Os códigos da história e do futuro da humanidade? Sim, sem dúvida. Mas eles não têm pressa em partilhar este conhecimento nem sequer com os "seus", quanto mais com aqueles que são obviamente classificados como estando no rebanho epistemológico.

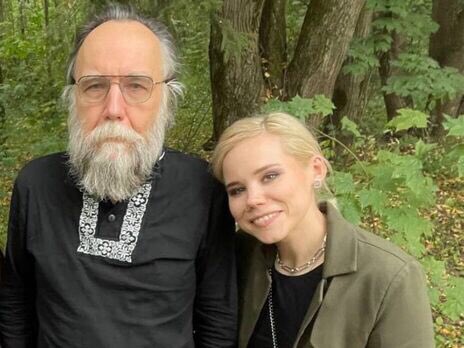

Na Rússia, a resposta a esta questão é dada pelo tradicionalismo Russo. O pai de Daria Dugina dedicou a sua série de vinte e quatro volumes de obras, Noomachia, ao estudo do Logos das civilizações, aos paradigmas da história humana. E Daria cresceu com isso, assimilando desde muito cedo o gosto pela Tradição e pelas ontologias verticais. Daria nasceu e cresceu numa família de filósofos da qual foi e continua a ser uma parte orgânica e integral. É uma eterna estrela em ascensão do pensamento russo. Todas as questões mais agudas levantadas pela modernidade tóxica e pela pós-modernidade do crepúsculo ocidental são respondidas pelos grandes tradicionalistas do século XX: René Guénon, Julius Evola, Mircea Eliade, Ernst Jünger, Lucian Blaga [romeno, 1895-1961], Emile Cioran, Louis Dumont [1911-198], Georges Dumezil, Alain de Benoist [n.1943, na fotografia com Daria] e dezenas de outros pensadores refinados.

Ele [Alexander Dugin] via os tradicionalistas como os pioneiros da Mente na história do século XX, que tentaram compreender o afundamento do navio da humanidade como uma transição do paradigma espiritual da Tradição (Antiguidade, Idade Média e Renascimento) para o paradigma materialista, individualista e anti-hierárquico da Idade Moderna, e depois para o paradigma em erosão da Idade Moderna que é a Idade Pós-Moderna.

Natalia Melentyeva (n. 22.IX.1957), com Alexander Dugin, a mãe de Daria.

A minha filha, Daria Platonova Dugina, interessou-se profundamente por todos estes temas. Dedicou-lhes artigos, relatórios, textos, fragmentos da sua dissertação inacabada. Num futuro próximo, espero publicar um livro com os seus textos filosóficos e histórico-filosóficos (relatórios, artigos, excertos).

Daria seguiu os seus pais tradicionalistas que, por sua vez, dedicaram toda a sua vida a analisar, traduzir, expor e ensinar as doutrinas tradicionalistas e a sua interpolação em vários domínios das ciências humanas - filosofia, sociologia, ciência política, história da filosofia, ciência, arte, teoria das relações internacionais, etc. - e ao estudo da história da filosofia. - e ao estudo da história da filosofia.

A minha referência às duas tendências intelectuais da modernidade - o deleuzianismo e as ontologias orientadas para o objecto - não é acidental. Como referi, a nossa condição actual exige um esforço mental sólido: não apenas um acto mental isolado de decifração e actualização da paisagem intelectual da modernidade, mas uma penetração determinada, profunda, diria mesmo iniciática, na essência da luta intelectual contemporânea. É uma luta, um confronto de mentes no mundo contemporâneo, uma verdadeira batalha ou Guerra das Mentes, Noomachia, como lhe chamou Alexander Dugin. O que é mais surpreendente e inesperado para o observador superficial é que esta guerra está cheia de batalhas, confrontos, lutas perdidas e ganhas, travadas com inteligência intelectual, manobras enganadoras, lavagem cerebral e desinformação intelectual. Actualmente, na retórica oficial da ciência política, fala-se de guerras mentais, ou seja, a mesma guerra da mente, a guerra do espírito [ou das mentes de almas-espíritos em confronto].

Assim, os nossos inimigos nesta guerra mental sabem muito bem o preço de um pensamento, o preço de uma ideia, o preço de um projecto. Mesmo Arthur Rimbaud, que dizia que "a batalha espiritual é tão feroz como as batalhas de um exército", sabia-o bem.

Nós, os filósofos da Tradição, os filósofos tradicionalistas, que soubemos discernir a estratégia do mundo moderno e reconhecer os paradigmas do Moderno e do Pós-Moderno que nos são estranhos, participamos nesta batalha feroz. Eles são-nos impostos pela civilização Ocidental moderna, com os seus percursos históricos particulares, os seus princípios e valores: liberalismo, individualismo, anti-hierarquia, materialismo. Estes princípios não são inofensivos. Em última análise, são desumanos e, de uma forma ou de outra, conduzem à destruição do homem e ao apagamento da humanidade do Livro da Vida.

Daria Dugina estava na vanguarda da guerra das inteligências, na "fronteira" intelectual, como gostava de dizer, no espaço das batalhas dos paradigmas, das ideias, das civilizações; era um verdadeiro cavaleiro da frente intelectual, um verdadeiro "filósofo-guardião", como Platão chamava aos filósofos, porque guardavam o que o ser humano tem de mais elevado: a sua dignidade intelectual, o seu direito à liberdade, ao pensamento, à protecção dos mais altos valores humanos, ao acesso, subindo a escada da contemplação dos mais altos princípios, e que no seu todo no Platonismo se chama Verdade, Bem, Justiça, Beleza, Bondade.» Que brilhem mais em nós!

LUX-AMOR!

********

Philosophy as Destiny, by the mother of Daria, Natalia Melentyeva. Translation from russian by Lorenzo Maria Pacini.

«Life in today's world presupposes and even requires an enormous effort on our part, not only in worldly matters and outward movements. Above

all, it requires an effort of the mind, of thought - a mental effort, a

"mental doing" as it was called in the monastic tradition of the "holy

fathers", with this praxis of the Mind is necessary not only to make a

"distinction", diacrisis, as the Greek Platonists used to say, to distinguish one from

the other - the precious from the non-precious, the good from the bad,

the casual from the fatal, but for something much greater and more

significant... We live in a damaged, twisted world, in a broken

civilisation whose backbone is broken, as is its perception of vertical

and hierarchical superiority. An intelligent effort is needed to restore

the proportions of this intelligent hierarchical world, the model for which was created by Plato, and that is Platonism.

Daria Dugina chose the pseudonym Platonov and devoted herself to the

study of Platonism and Platonic philosophers. The american A. Whitehead

once said that the entire world's philosophy is nothing but Plato's

margin notes. By engaging with Platonism - we get to the centre of the

typhoon, to the heart of the problem of meaning generation, of the

creation of thought structures, of the mind, of history, of cultures, of

civilisations... Dasha knew this and deliberately chose this path. The

way of the mind is dangerous. People fear the mind like fire. Once, the

city authorities of Athens had the wisest thinker of Greece and of all

humanity, Socrates, executed; the people of Alexandria murdered the

Neo-Platonic philosopher Hypatia. Today, the elites of the Western world

hate free thinking in a vicious and totalitarian manner. They kill and

intend to kill thinkers, philosophers, sages, prophets, geniuses - all

those who do not think about the fate of mankind in unison with the

group of villains who have taken over the modern global discourse, who

are about to shut down the Human Project altogether, turning it into a

clone, a computer, information in the cloud. Daria Dugina knew that this

reasoned obscurantism had to be countered first and foremost by Mind:

thought, idea, concept, design. She chose Platonism as the focus of this struggle.

Plato created an intelligent and coherent two-storey world, in which the

ideas, models, forms of things and events of the world floated in the

upper storey, while in the lower storey dwelt matter and things

themselves, which existed by contemplating the ideas-Logos and imitating

them as their celestial models. Thus was constructed the hierarchy of

Heaven and Earth, a hierarchy of ideas at the head of which shone the

idea of the Good, or the One: the inexpressible, the inexpressible,

beyond all that could or could not be thought. Platonism described an

intellectual and intelligent structure of the world, open from above. It

placed man at the centre of a vertical hierarchy as a kind of mediator

between worlds. By contemplating ideas, man ensured that the world was

constructed and things were produced, echoing the celestial archetypes.

This model of the world has existed for millennia. Its structures,

hierarchies, scales of ascent and descent are reflected in all the

world's religions. Man in it is a 'being who ascends' (towards Spirit,

Goodness, Truth, Beauty, Justice, the One), and sometimes returns

(Plato's Myth of the Cave) and climbs back up Jacob's ladder, the ladder

of spiritual perfection. This ascent of man, his perfection, his

transubstantiation, is the goal of life.

Becoming and the dark side of freedom

However, the world deteriorates over time, man

becomes foolish. In one way or another came the Modern and then the

Postmodern, which is partly what we find ourselves in today. The 20th

century French postmodernist Gilles Deleuze falsifies Plato - only in

the margins of his writings - fundamentally distorting the Platonic

image of the world. Deleuze argues that Platonism was not talking about

the dualism between ideas and matter, but about the duality of matter

itself: that which welcomes ideas, that is, copies, and that which

avoids the influence of ideas altogether, hides from them, escapes the

influence of the intelligent model, the Logos. In the world, our most

popular Western philosopher tells us, there are things that slip away,

avoiding any form, any definition. He calls this 'pure becoming',

'infinite', 'shadow of the copy', 'copy without the original' or

'simulacrum'. According to Deleuze, such indefinable things and persons,

who elude the idea, the Logos, are not completely without measure, but

this measure is not above them, but below them, in the subsoil of their

existence. They do not remain in the shadow of the One Creator, of the

highest heavenly meanings, but under the spell, the hypnosis of a mad

element that lives below that order which in the Platonic universe

things receive from the Logos, the world of Mind and ideas.

Deleuze's two worlds: copies and simulacra.

Thus Deleuze establishes two worlds: one governed

by the mundane Mind, which receives models and forms from the celestial

spheres, and this world appears to Deleuze as decrepit, not free, not

dynamic, totalitarian. It is the world of a fixed reality, of a fixed

certainty, and therefore the world of 'pauses' and 'stops', with a

clumsy language to describe it, to speak of it.

The second world, new and beautiful, comes to the aid of the old, bringing with it flowing meanings, a flowing, light element of flux, and a 'rebellious becoming' without pauses and stops.

Through the immobility and rigidity of the old

hierarchical world of ideas and things (it is not difficult to guess

that this is the Platonic world of double arguments), Deleuze's second

world, the world of paradoxical becoming, appears like a ghost, where

everything is fluid to the point that the meanings of past and future

are identical, where before and after, plus and minus, cause and effect,

excess and deficiency, crime and punishment merge in an inexplicable

concord and inter-transformation. We enter a world without limits that

are transgressed - hence the world of crime, of lawlessness. It is a

world of mutual reversibility of events, i.e. a place where reason is

problematised. Deleuze likes the idea that alongside formalised things

and beings there are indeterminate events and that on their surface even

smaller events, which he calls 'effects', are stirring. Effects are

fluid, light, ungrounded, arbitrary, spontaneous.

Man as event

"What is a wound on the surface of the body?",

Deleuze asks himself. Is it a dense thing with its own status? Is it an

effect, a small event that 'does not even exist, but only persists for a

while in its manifestation', becomes, possesses a minimum of being.

What are we ourselves? Isn't human life, including our self, our inner summit, which we revere as subject, our world, our dream, Deleuze suggests, just a blind churning on the surface of some event? We are only a slight creaking on the surface of being. A rustling of paper, a kind of mist that moves at the edges of things.

What is the redness of iron, the redness of the face?, asks Deleuze. It is a mixture of reds and greens. We too are mixtures, mingling, for better or worse, with things.

Deleuze's 'world of effects' mixes and spreads. In it we move in an infinite Aeon of becoming.

There is no All in the world,' argues the master

of French rhetoric, 'that orders and is responsible for the

metamorphosis of things and ourselves. There is no reason in the world.

What is required of us is not to be, but to slip.

Chaosmos.

Deleuze's world is a journey towards Chaosmos, with the loss of names and the negation of all permanence, including

knowledge (because 'permanence needs peace and God', as Deleuze notes,

'and we cannot give you that'). It is a universe without verticality,

where the symbol of the tree as a vertical axis and hierarchy is

replaced by the image of a rhizome, a tuber like a potato, which sprouts

casually and unconsciously to the side, to the side, down, sometimes

even up. This is the world of the infinite, the apeiron (ἄπειρον) - what

the ancient Greeks particularly hated, as opposed to the limit, the

peras (πέρας), which completed, fixed the thing.

Deleuzian becoming implies a fusion of language,

where nouns are swept away by verbs as more fluid entities, and where in

becoming everything dissolves and disappears. Deleuze's actual world of

becoming is the world of language that disintegrates and mutates in the

process of this disintegration. Since the denotative is abolished even

before Deleuze's philosophy, in the structuralism of F. de Saussure,

from which Deleuze distances himself, reality is transformed in him into

a purely linguistic residuality, in which the semantic fabric, the

field of meaning of being, dissolves and disappears, involving Man as

the owner and manager of language in this extinction. Acquired in pure

becoming, post-language is transformed into an inexplicable bellow -

into a flash of 'effect' on the surface of the molten smoothness of

matter that collapses into infernal depths. Daria Dugina dedicated her

essay Black Deleuze to Deleuze and has often referred to him and his

philosophy in her speeches, interventions and lectures.

Predatory Things and the Empty Subject Ltd.

The programme of man's dissolution,

destabilisation and dissolution of the world itself is today being

elaborated not only in the extravagant and perverse programmes of the

Deleuze school, but also in the post-Deleuzian philosophical groups of

contemporary Western 'hyper-materialist realists' or 'object-oriented

ontologists' (OOO), such as R. Negarestani, N. Land, G. Harman, R.

Brassier, C. Meyasu and others. These philosophers explain that man, in

classical Western philosophy, unjustifiably appears to us as too

upright, authoritarian, arrogant and self-righteous. However, compared

to artificial intelligence, for example, it is absolutely imperfect and

unmanageable. It is therefore pointless and dangerous to continue to

indulge man in his illusion of being the administrator of the universe

and the architect of social progress. Man is too burdened by the Logos.

Why are we so sure, ask the OOO representatives, that man is the measure

of things, the main pole of correlation? There is Nothingness and its

circularity, which is called 'becoming'. Henceforth, the world of the

being formerly called 'man' is characterised by indeterminacy,

blurriness, fluidity, 'permeability', chaoticity, and this concerns not

only the events of his life, but also

the state of his fragile and unstable self.

But what is truly solid and reliable in the world

are cosmic objects, simple things, the Earth, its core, compressed in

the prison of an icy crust. Objects, though phenomenologically

indemonstrable, are also practically attainable: if only we extinguish

our human Dasein, they will reveal themselves to us in a completely

unexpected way, most likely as monsters, according to Graham Harman, of

Weird Realism. While our human presence is still persistent, the noomen

are unreachable. They (the noomen, the things) live in a radically

external (hellish) way, inaccessible to us, and quite possibly quite

predatory, and we take advantage of this, naively considering ourselves

their masters and mistresses, but there is a great rebellion of things

to come, as Bruno Latour said. Man is nothing, with all his ephemeral

claims, capacities, projects and illusions; objects must be freed from

man, left free to create, to follow their own cosmic paths and

trajectories; man must be removed from the path of the Earth's core, for

example, to free the nuclear demon within the Earth, so that this hot,

glowing solar essence can unite in a cosmic dance with the Sun - this is

what the Iranian-born American philosopher Reza Negarestani tells us, echoing the British philosopher Nick Land.

Daria Dugina has studied the texts of contemporary

object-oriented ontologists very carefully, polemising with them in

articles and speeches. There was also a curious incident. Daria once

participated in an on-line presentation of Negarestani's book in Moscow.

This incident became well known because in the middle of an

intellectual discussion, one of Dasha's admirers asked for her hand and

heart. Daria kindly promises to consider this proposal, but only after

the suitor of conservative-traditionalist ideas manages to master the

philosophy opposite hers and learns R. Negarestani's Cyclonopedia by

heart.

Attack on surfaces.

The theme of the insolvency and vanity of man in

the representatives, as we have shown, is synchronised with that of the

dissolution of man in Deleuze, the subtle philosopher, in which the true

will is proclaimed not for things and huge cosmic bodies and objects,

but for the weak surface effects of all these properties. Taking in the

panorama of modern Western philosophy, we see before us the different

flanks of a single front attacking our spiritual tradition - Platonic,

Christian, traditional. In this invasion of modern Western philosophy

upon us, there are no verticals, no hierarchies, no forms, no ideas, no

values, no objects, no essences, no causes, no qualities, no schemes, no

goals, no language, no depth, no height, no freedom, no spirit, no God.

There is no place for man either. He is commanded not to go deep, not

to look high and far, not to dream, not to project, not to think, but to

slip and dissolve, to rustle and not to think too much of himself. We

are commanded, even ordered, to stay on the surface of things, to glide

along the surface of events, to follow trends, to follow agendas.

War of wits.

I said "we are commanded"! Yes, that's right!

Behind the soft rustle of Deleuze's wild speech, we traditionalists feel

the heavy tread of the totalitarian imperative. Does this not mean that

there is someone in the world who understands what rules are offered to

us, and that in the world there are not orders of things per se, but

orders of interpretations? Under the guise of a seemingly random

philosophical game, are requirements imposed on things and ourselves,

hence principles and rules by which someone glues us to certain

standards of perception and behaviour? Yes, this is indeed the case,

and our intellectual adversaries in the West understand this. Just as

the cardinal law of geopolitics states that 'He who controls the

Heartland (Eurasia) owns the world', so here the formula works: 'He who

controls the discourse, establishes the meta-language, rules over everything'.

Are the paradigms - the keys to worldviews, civilisations and cultures - known in the West? The codes of humanity's history and future? Yes, without a doubt. But they are in no hurry to share this knowledge even with 'their own', let alone those who are obviously classified among the epistemological herd.

In Russia, the answer to this question is offered

by Russian traditionalism. Daria Dugina's father dedicated his 24-volume

series of works, Noomachia, to the study of the Logos of civilisations,

the paradigms of human history. And Daria grew up with it, assimilating

from an early age a taste for Tradition and vertical ontologies. Daria

was born and raised in a family of philosophers of which she was and

still is an organic and integral part. She is an eternal rising star of

Russian thought. All the sharpest questions thrown up by toxic modernity

and the post-modernity of the western twilight are answered by the

great traditionalists of the 20th century: René Guénon, Julius Evola,

Mircea Eliade, Ernst Jünger, Lucian Blaga, Emile Cioran, Louis Dumont,

Georges Dumezil, Alain de Benoit and dozens of other refined thinkers.

He saw the traditionalists as those pioneers of Mind in 20th century history, who tried to understand the sinking of the ship of humanity as a transition from the spiritual paradigm of Tradition (Antiquity, the Middle Ages and the Renaissance) to the materialistic, individualistic and anti-hierarchical paradigm of the Modern Age, and then to the eroding paradigm of the Modern Age that is the Postmodern Age.

My daughter, Daria Platonova Dugina, was deeply interested in all these topics. She dedicated articles, reports, texts, fragments of her unfinished dissertation to them. In the near future, I hope to publish a book with her philosophical and historical-philosophical texts (reports, articles, excerpts).

Daria followed her traditionalist parents who, in

turn, devoted their entire lives to analysing, translating, expounding,

and teaching traditionalist doctrines and their interpolation into

various fields of the human sciences - philosophy, sociology, political

science, history of philosophy, science, art, theory of international

relations, etc. - and to the study of the history of philosophy.

My reference to the two intellectual trends of

modernity - Deleuzianism and object-oriented ontologies - is not

accidental. As mentioned, our current condition requires a solid mental

effort: not just a detached mental act of deciphering and actualising

the intellectual landscape of modernity, but a determined, deep, I would

say initiatory, penetration into the essence of the contemporary

intellectual struggle. It is a struggle, a confrontation of minds in the

contemporary world, a real battle or War of the Minds, Noomachia,

as Alexander Dugin called it. What is most surprising and unexpected to

the superficial observer is that this war is full of battles, clashes,

battles lost and won, delivered with intellectual intelligence,

deceptive manoeuvres, brainwashing and intellectual disinformation.

Today, in the official rhetoric of political science, we speak of

'mental wars', i.e. the same 'war of the mind', the war of the spirit.

Thus, our enemies in this war of the mind know

very well the price of a thought, the price of an idea, the price of a

project. Even Arthur Rimbaud, who said that 'the spiritual battle is as

fierce as the battles of an army', knows this well.

We, the philosophers of tradition, traditionalist

philosophers, who have been able to discern the strategy of the modern

world and recognise the paradigms of the Modern and Postmodern that are

alien to us, participate in this fierce battle. They are imposed on us

by modern Western civilisation, with its particular historical paths,

its principles and values: liberalism, individualism, anti-hierarchy,

materialism. These principles are not harmless. Ultimately, they are

inhuman and, in one way or another, lead to the destruction of man

and the erasure of humanity from the The Book of Life.

Daria Dugina was in the vanguard of the war of

wits, on the intellectual 'frontier', as she liked to say, in the space

of the battles of paradigms, ideas, civilisations; she was a true knight

of the intellectual front, a true philosopher-guardian, as Plato

called philosophers, because they guarded the highest thing man has: his

intellectual dignity, his right to freedom, to thought, to the

protection of the highest human values, to access, by climbing the

ladder of contemplation of the highest principles, the entire volume of

what in Platonism is called Truth, Good, Justice, Beauty, Goodness.

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário